Java and Perl Are Examples Oflanguages

I first heard of Perl when I was in middle school in the early 2000s. It was one of the world's most versatile programming languages, dubbed the Swiss army knife of the Internet. But compared to its rival Python, Perl has faded from popularity. What happened to the web's most promising language?

Perl's low entry barrier compared to compiled, lower level language alternatives (namely, C) meant that Perl attracted users without a formal CS background (read: script kiddies and beginners who wrote poor code). It also boasted a small group of power users ("hardcore hackers") who could quickly and flexibly write powerful, dense programs that fueled Perl's popularity to a new generation of programmers.

A central repository (the Comprehensive Perl Archive Network, or CPAN) meant that for every person who wrote code, many more in the Perl community (the Programming Republic of Perl) could employ it. This, along with the witty evangelism by eclectic creator Larry Wall, whose interest in language ensured that Perl led in text parsing, was a formula for success during a time in which lots of text information was spreading over the Internet.

As the 21st century approached, many pearls of wisdom were wrought to move and analyze information on the web. Perl did have a learning curve–often meaning that it was the third or fourth language learned by adopters–but it sat at the top of the stack.

"In the race to the millennium, it looks like C++ will win, Java will place, and Perl will show," Wall said in the third State of Perl address in 1999. "Some of you no doubt will wish we could erase those top two lines, but I don't think you should be unduly concerned. Note that both C++ and Java are systems programming languages. They're the two sports cars out in front of the race. Meanwhile, Perl is the fastest SUV, coming up in front of all the other SUVs. It's the best in its class. Of course, we all know Perl is in a class of its own."

Then came the upset.

The Perl vs. Python Grudge Match

Then Python came along. Compared to Perl's straight-jacketed scripting, Python was a lopsided affair. It even took after its namesake, Monty Python's Flying Circus. Fittingly, most of Wall's early references to Python were lighthearted jokes at its expense.

Well, the millennium passed, computers survived Y2K, and my teenage years came and went. I studied math, science, and humanities but kept myself an arm's distance away from typing computer code. My knowledge of Perl remained like the start of a new text file: cursory, followed by a lot of blank space to fill up.

In college, CS friends at Princeton raved about Python as their favorite language (in spite of popular professor Brian Kernighan on campus, who helped popularize C). I thought Python was new, but I later learned it was around when I grew up as well, just not visible on the charts.

By the late 2000s Python was not only the dominant alternative to Perl for many text parsing tasks typically associated with Perl (i.e. regular expressions in the field of bioinformatics) but it was also the most proclaimed popular language, talked about with elegance and eloquence among my circle of campus friends, who liked being part of an up-and-coming movement.

Side By Side Comparison: Binary Search

Despite Python and Perl's well documented rivalry and design decision differences–which persist to this day–they occupy a similar niche in the programming ecosystem. Both are frequently referred to as "scripting languages," even though later versions are retro-fitted with object oriented programming (OOP) capabilities.

Stylistically, Perl and Python have different philosophies. Perl's best known mottos is " There's More Than One Way to Do It". Python is designed to have one obvious way to do it. Python's construction gave an advantage to beginners: A syntax with more rules and stylistic conventions (for example, requiring whitespace indentations for functions) ensured newcomers would see a more consistent set of programming practices; code that accomplished the same task would look more or less the same. Perl's construction favors experienced programmers: a more compact, less verbose language with built-in shortcuts which made programming for the expert a breeze.

During the dotcom era and the tech recovery of the mid to late 2000s, high-profile websites and companies such as Dropbox (Python) and Amazon and Craigslist (Perl), in addition to some of the world's largest news organizations (BBC, Perl) used the languages to accomplish tasks integral to the functioning of doing business on the Internet.

But over the course of the last 15 years, not only how companies do business has changed and grown, but so have the tools they use to have grown as well, unequally to the detriment of Perl. (A growing trend that was identified in the last comparison of the languages, "A Perl Hacker in the Land of Python," as well as from the Python side a Pythonista's evangelism aggregator, also done in the year 2000.)

Perl's Slow Decline

Today, Perl's growth has stagnated. At the Orlando Perl Workshop in 2013, one of the talks was titled "Perl is not Dead, It is a Dead End," and claimed that Perl now existed on an island. Once Perl programmers checked out, they always left for good, never to return. Others point out that Perl is left out of the languages to learn first–in an era where Python and Java had grown enormously, and a new entrant from the mid-2000s, Ruby, continues to gain ground by attracting new users in the web application arena (via Rails), followed by the Django framework in Python (PHP has remained stable as the simplest option as well).

In bioinformatics, where Perl's position as the most popular scripting language powered many 1990s breakthroughs like genetic sequencing, Perl has been supplanted by Python and the statistical language R (a variant of S-plus and descendent of S, also developed in the 1980s).

In scientific computing, my present field, Python, not Perl, is the open source overlord, even expanding at Matlab's expense (also a child of the 1980s, and similarly retrofitted with OOP abilities). And upstart PHP grew in size to the point where it is now arguably the most common language for web development (although its position is dynamic, as Ruby and Python have quelled PHP's dominance and are now entrenched as legitimate alternatives.)

While Perl is not in danger of disappearing altogether, it is in danger of losing cultural relevance, an ironic fate given Wall's love of language. How has Perl become the underdog, and can this trend be reversed? (And, perhaps more importantly, will Perl 6 be released!?)

How I Grew To Love Python

Why Python, and not Perl? Perhaps an illustrative example of what happened to Perl is my own experience with the language.

In college, I still stuck to the contained environments of Matlab and Mathematica, but my programming perspective changed dramatically in 2012. I realized lacking knowledge of structured computer code outside the "walled garden" of a desktop application prevented me from fully simulating hypotheses about the natural world, let alone analyzing data sets using the web, which was also becoming an increasingly intellectual and financially lucrative skill set.

One year after college, I resolved to learn a "real" programming language in a serious manner: An all-in immersion taking me over the hump of knowledge so that, even if I took a break, I would still retain enough to pick up where I left off. An older alum from my college who shared similar interests–and an experienced programmer since the late 1990s–convinced me of his favorite language to sift and sort through text in just a few lines of code, and "get things done": Perl. Python, he dismissed, was what "what academics used to think." I was about to be acquainted formally.

Before making a definitive decision on which language to learn, I took stock of online resources, lurked on PerlMonks, and acquired several used O'Reilly books, the Camel Book and the Llama Book, in addition to other beginner books. Yet once again, Python reared its head, and even Perl forums and sites dedicated to the language were lamenting the digital siege their language was succumbing to. What happened to Perl? I wondered. Ultimately undeterred, I found enough to get started (quality over quantity, I figured!), and began studying the syntax and working through examples.

But it was not to be. In trying to overcome the engineered flexibility of Perl's syntax choices, I hit a wall. I had adopted Perl for text analysis, but upon accepting an engineering graduate program offer, switched to Python to prepare.

By this point, CPAN's enormous advantage had been whittled away by ad hoc, hodgepodge efforts from uncoordinated but overwhelming groups of Pythonistas that now assemble in Meetups, at startups, and on college and corporate campuses to evangelize the Zen of Python. This has created a lot of issues with importing (pointed out by Wall), and package download synchronizations to get scientific computing libraries (as I found), but has also resulted in distributions of Python such as Anaconda that incorporate the most important libraries besides the standard library to ease the time tariff on imports.

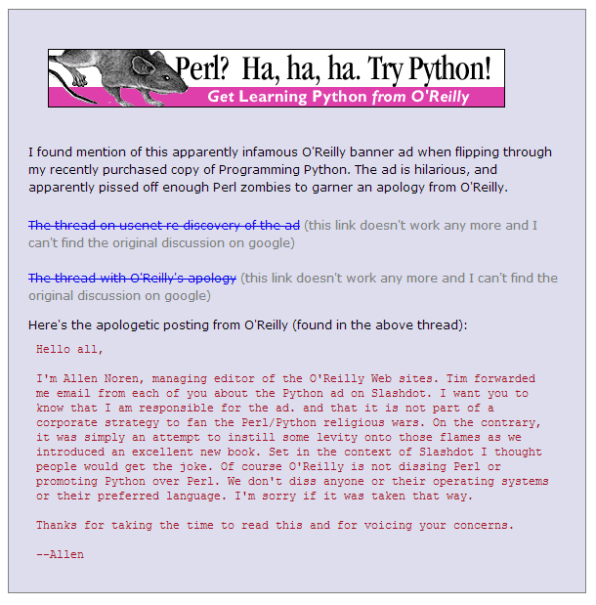

As if to capitalize on the zeitgiest, technical book publisher O'Reilly ran this ad, inflaming Perl devotees.

By 2013, Python was the language of choice in academia, where I was to return for a year, and whatever it lacked in OOP classes, it made up for in college classes. Python was like Google, who helped spread Python and employed van Rossum for many years. Meanwhile, its adversary Yahoo (largely developed in Perl) did well, but comparatively fell further behind in defining the future of programming. Python was the favorite and the incumbent; roles had been reversed.

So after six months of Perl-making effort, this straw of reality broke the Perl camel's back and caused a coup that overthrew the programming Republic which had established itself on my laptop. I sheepishly abandoned the llama. Several weeks later, the tantalizing promise of a new MIT edX course teaching general CS principles in Python, in addition to numerous n00b examples, made Perl's syntax all too easy to forget instead of regret.

Measurements of the popularity of programming languages, in addition to friends and fellow programming enthusiasts I have met in the development community in the past year and a half, have confirmed this trend, along with the rise of Ruby in the mid-2000s, which has also eaten away at Perl's ubiquity in stitching together programs written in different languages.

While historically many arguments could explain away any one of these studies–perhaps Perl programmers do not cheerlead their language as much, since they are too busy productively programming. Job listings or search engine hits could mean that a programming language has many errors and issues with it, or that there is simply a large temporary gap between supply and demand.

The concomitant picture, and one that many in the Perl community now acknowledge, is that Perl is now essentially a second-tier language, one that has its place but will not be the first several languages known outside of the Computer Science domain such as Java, C, or now Python.

The Future Of Perl (Yes, It Has One)

I believe Perl has a future, but it could be one for a limited audience. Present-day Perl is more suitable to users who have worked with the language from its early days, already dressed to impress. Perl's quirky stylistic conventions, such as using $ in front to declare variables, are in contrast for the other declarative symbol $ for practical programmers today–the money that goes into the continued development and feature set of Perl's frenemies such as Python and Ruby. And the high activation cost of learning Perl, instead of implementing a Python solution.

Ironically, much in the same way that Perl jested at other languages, Perl now finds itself at the receiving end. What's wrong with Perl, from my experience? Perl's eventual problem is that if the Perl community cannot attract beginner users like Python successfully has, it runs the risk of become like Children of Men, dwindling away to a standstill; vast repositories of hieroglyphic code looming in sections of the Internet and in data center partitions like the halls of the Mines of Moria. (Awe-inspiring and historical? Yes. Lively? No.)

Perl 6 has been an ongoing development since 2000. Yet after 14 years it is not officially done, making it the equivalent of Chinese Democracy for Guns N' Roses. In Larry Wall's words: "We're not trying to make Perl a better language than C++, or Python, or Java, or JavaScript. We're trying to make Perl a better language than Perl. That's all." Perl may be on the same self-inflicted path to perfection as Axl Rose, underestimating not others but itself. "All" might still be too much.

Absent a game-changing Perl release (which still could be "too little, too late") people who learn to program in Python have no need to switch if Python can fulfill their needs, even if it is widely regarded as second or third best in some areas. The fact that you have to import a library, or put up with some extra syntax, is significantly easier than the transactional cost of learning a new language and switching to it. So over time, Python's audience stays young through its gateway strategy that van Rossum himself pioneered, Computer Programming for Everybody. (This effort has been a complete success. For example, at MIT Python replaced Scheme as the first language of instruction for all incoming freshman, in the mid-2000s.)

Python Plows Forward

Python continues to gain footholds one by one in areas of interest, such as visualization (where Python still lags behind other language graphics, like Matlab, Mathematica, or the recent d3.js), website creation (the Django framework is now a mainstream choice), scientific computing (including NumPy/SciPy), parallel programming (mpi4py with CUDA), machine learning, and natural language processing (scikit-learn and NLTK)… and the list continues.

While none of these efforts are centrally coordinated by van Rossum himself, a continually expanding user base, and getting to CS students first before other languages (such as even Java or C), increases the odds that collaborations in disciplines will emerge to build a Python library for themselves, in the same open source spirit that made Perl a success in the 1990s.

As for me? I'm open to returning to Perl if it can offer me a significantly different experience from Python (but "being frustrating" doesn't count!). Perhaps Perl 6 will be that release. However, in the interim, I have heeded the advice of many others with a similar dilemma on the web. I'll just wait and C.

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/3026446/the-fall-of-perl-the-webs-most-promising-language

0 Response to "Java and Perl Are Examples Oflanguages"

Postar um comentário